Yuzivka

A settlement that later became the city of Donetsk. Founded, built and industrialized by Welsh businessman John Hughes.

1869

Fonts:

Extatica (Bold)

Designer:

A settlement that later became the city of Donetsk. Founded, built and industrialized by Welsh businessman John Hughes.

Probably everyone has heard the story that the Soviet Union built up the abandoned Donbas from scratch and made it the industrial center of the country. But everyone knows where this story comes from. The myth, created during Stalin’s regime and further supported by Putin, could be easily destroyed if we look a little further back into the 19th century. It turns out that Donetsk was industrialized before the Communists came to power, and in fact, the Welshman John Hughes was the one who did it.

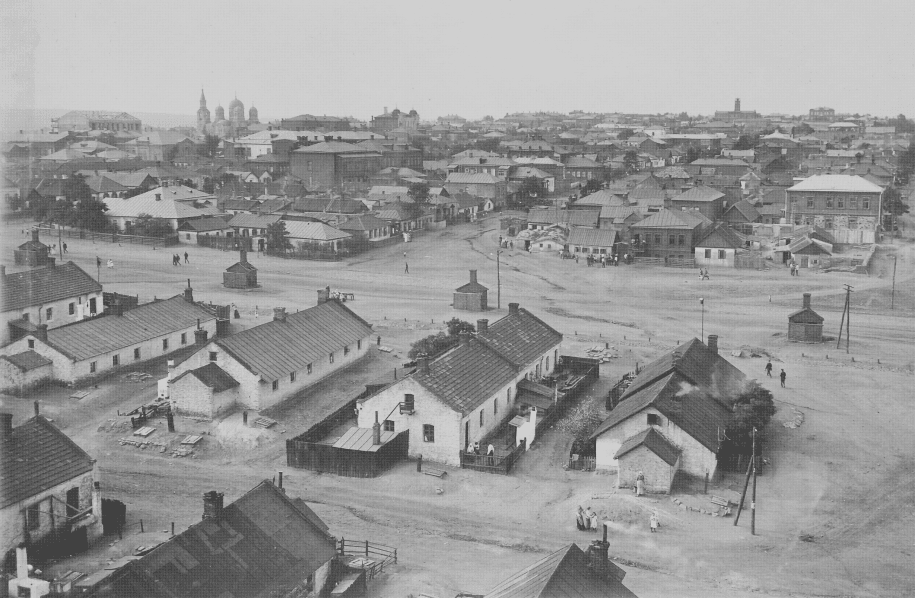

To start the story about Yuzivka, it’s worth mentioning what was happening in the Donbas region before John Hughes arrived. There were separate settlements here called slobodas (a settlement or a town district of people free of the power of boyars): Oleksandrivka, Hryhorivka, several villages, and Ovechyi hamlet, founded two centuries earlier by the Zaporizhian Cossacks. Later, Ukrainian peasants played an important role in the industrialization of Donbas.

Yuzivka was founded in 1869.

A Welsh businessman bought the right to build a rail manufacturing plant from Russian Prince Sergey Kochubey. But it turned out that the area had significant coal deposits. Therefore, clever Hughes started a full-cycle production that has been characteristic of the Donbas region: coal - coke - metal.

For this purpose, the Novorossiysk Society of Coal, Iron and Rail Production was established, which became a leader in steel production in the Russian Empire at the beginning of the 19th century. The Welsh supplied the village with electricity, laid a railroad that connected the Hughes’ plants with Kharkiv and Kursk, and built facilities.

Hundreds of Welsh, English, French, Belgians, and Germans came here to work as engineers and craftsmen in prestigious and highly paid jobs. Several generations of Europeans lived here before the Bolsheviks came in the early 1920s.

Local peasants worked at the mines and blast furnace plant. It was a seasonal job for them, and they would return home for the harvest. These people are the heroes of another well-known Soviet myth: about entire generations of proletarians who supposedly worked in factories. In fact, Donbas was developed by the Ukrainian peasantry. The mine gave them the opportunity to earn a penny and feed a large family.

Yuzivka was developed under the influence of Western culture. At the time of its foundation, it was inhabited by 164 people, and in 1907 (38 years later) by 32 thousand people. The Hughes’ family took care of everything.

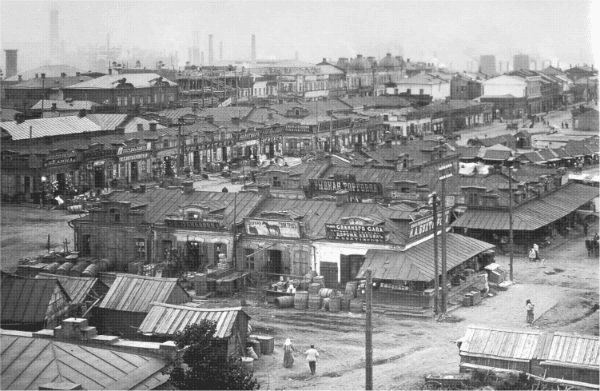

There were shops, a Sunday market, inns and German pubs, a hotel, and a post office. The businessman even set up a police department that was funded by the company. The first street - the main street of Yuzivka (now Artema Street) — was built up with shops, restaurants, hotels, as well as banks and offices where businessmen sold coal and metal.

Western businessmen developed not only Donetsk. Lysychansk, for example, not incidentally, was called the “tenth Belgian province.” Then the Bolsheviks came. They seized the territory, nationalized (took away) the facilities, stole the achievements and created a myth.

The same scenario has been used by Russia to occupy part of Donbas since 2014.

But despite all the attempts by Russians to depict Donbas as their historic territory, history is stronger than myths. And the history of the European, Ukrainian Donbas will eventually prevail.

All Ukrainians believe in it and are waiting for Donbas to return home.

Fonts:

Extatica (Bold)

Next letter and event

Yuzivka

this project

in social

“Shchedryk” (The Little Swallow)

Crimean Tatars, Karaites and Krymchaks (qırımlılar, qaraylar)

Yizhak protytankovyi (Czech hedgehog)

Antonov AN-225 Mriya ("The Dream")

Lisova Pisnia (The Forest Song)

Falz-Fein and his “Askania Nova”

Yrii (/'irij/: iriy), yndyk (/in'dik/: turkey) and yrod (/'irod/: Herod)

Falz-Fein and his “Askania Nova”

“Nasha armiia, nashi khranyteli” (“Our Army, Our Guardians”)

Shliakh iz variah u hreky (Route from the Varangians to the Greeks)

Zaporizka Sich (The Zaporizhian Host)

Volia — collective concept, most often translated as Freedom

Peresopnytske Yevanheliie (The Peresopnytsia Gospel)

Holodomor

Budynok “Slovo” (The Slovo Building, or "The Word")

Creative & Tech Online Institute

Медіа про дизайн, креатив і тех індустрії

Ukrainski sichovi striltsi (The Ukrainian Sich Riflemen, or the USS)

Aeneid by Ivan Kotliarevsky

Danylo Halytskyi

“Plyve kacha po Tysyni...” (“Swims the duckling, on the Tysa...”)

Khreshchenia Rusi (Christianization of Kyivan Rus’)

Holodomor

Kvitka Cisyk (Kasey Cisyk)

Falz-Fein and his “Askania Nova”

Volia — collective concept, most often translated as Freedom

“Yoi, nai bude!” (Ah, let it be!)

Peresopnytske Yevanheliie (The Peresopnytsia Gospel)

Yrii (/'irij/: iriy), yndyk (/in'dik/: turkey) and yrod (/'irod/: Herod)

Ivan Franko

Georgiy Gongadze

Peresopnytske Yevanheliie (The Peresopnytsia Gospel)