Yrii (/'irij/: iriy), yndyk (/in'dik/: turkey) and yrod (/'irod/: Herod)

The spelling of these distinctive Ukrainian words using the letter “и” (y: /ɪ/) reflects the originality and versatility of the Ukrainian language, which could have been lost after centuries of linguicide and Russification.

Fonts:

Kruk

Designer:

For many centuries, the Russians had wanted to destroy the Ukrainian language, and later, they tried to assimilate it to Russian for their imperial needs. Unfortunately, they did manage to change the way the Ukrainians communicated, but not for long. The Ukrainian language has not only survived, but is also experiencing a rapid rise. Although some authentic features of Ukrainian have been lost, its best linguistic traditions are gradually reviving.

The first phonetic system, which to this day serves as the basis for the Ukrainian orthography, was created by Ruska Triytsia (the Ruthenian Triad) — a Galician literary group led by Markiian Shashkevych that began a national and cultural revival in western Ukraine in the 19th century. It was due to the Spelling System of Shashkevych that Ukrainians claimed the unique letter “є” /je/, got rid of the Russian hard sign “ъ”, began to indicate the sound /ɪ/ with the letter “и” instead of the Russian “ы”, and also started using the letter combinations “йо” /jo/ and “ьо” /’o/. The formation of the literary register of Ukrainian was quite a nuisance for the Russians, who sought to destroy the language or at least make it similar to Russian.

The Russian Empire has engaged in acts of linguicide against Ukrainians for more than three centuries, starting out with direct repressions, such as the Valuev Circular of 1863 and the Ems Ukaz of 1876. These decrees aimed to ban Ukrainian-language publications and eradicate Ukrainian from the public sphere. Later, the Soviet authorities switched to more sophisticated methods, realizing that if a language cannot be suppressed, it can be distorted.

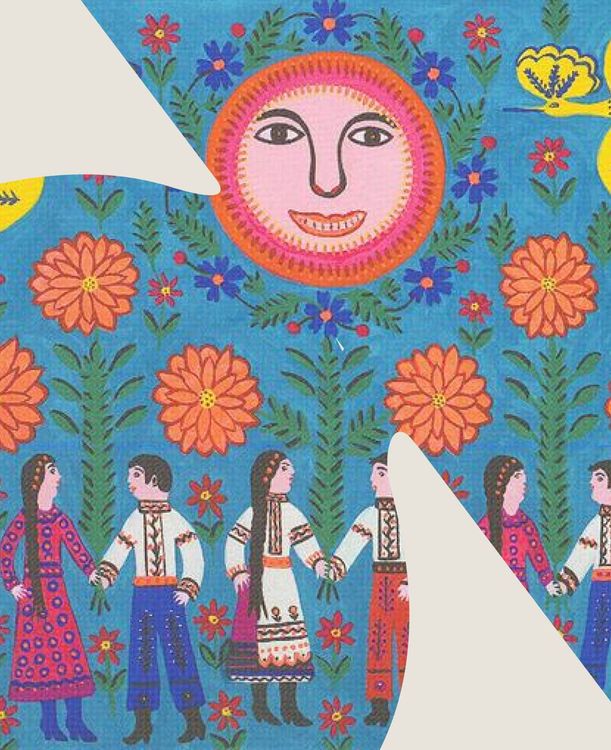

The next wave of repression hit the “Skrypnykivka,” which was the 1928 Spelling System of Skrypnyk, largely following after Shashkevych and normalizing the authentic phonetics of the Ukrainian language. According to Skrypnyk’s spelling, the Ukrainians pronounce ganok (porch), avdytoriia (auditorium, which is either a university classroom or figuratively its audience), proiekt (/projekt/: project), katedra (cathedra, cathedral, teacher’s lectern, or university department), yrii (iriy: a mythical place in Slavic mythology that is associated with paradise). The Skrypnykivka has become an idealized symbol of the Ukrainian cultural Renaissance; many linguists consider it an exemplary orthography.

Due to the uniqueness of the Skrypnykivka, the Soviet authorities called the spelling “nationalist” and adopted new language norms of 1933, the purpose of which was to artificially bring Ukrainian closer to Russian.

The Ukrainians were deprived of traditional Ukrainian sound combinations, banned from using the letter “ґ” /g/ and obliged to use toponyms “as accepted by the Soviet state authorities” — for example, Afiny /aˈfinɪ/ instead of Ateny /aˈtenɪ/ (Athens). Of course, after the collapse of the USSR, the Ukrainian linguists created new spelling systems, but they were only painful compromises between what Ukrainian should have been like and the people’s newly formed speaking habits after nearly a century of intensive Russification.

The Ukrainian language suffered for a long time abused by the Russian Empire, and later, from the Soviet influence.

Significant changes began with the independence of Ukraine. In 2019, the Cabinet of Ministers adopted the current version of the spelling, which brought back some of the Skrypnykivka’s norms and took into account the realities of the continuous development of Ukrainian.

Fonts:

Kruk

Details:

Yrii (/'irij/: iriy), yndyk (/in'dik/: turkey) and yrod (/'irod/: Herod)

Designer:

About font:

Next letter and event

Yrii (/'irij/: iriy), yndyk (/in'dik/: turkey) and yrod (/'irod/: Herod)

this project

in social

“Shchedryk” (The Little Swallow)

“Nasha armiia, nashi khranyteli” (“Our Army, Our Guardians”)

“Yak umru to pokhovaite...” (When I am dead, bury me...)

Ivan Franko

Chornobyl Disaster

Falz-Fein and his “Askania Nova”

Orlyk’s Constitution

Falz-Fein and his “Askania Nova”

Lisova Pisnia (The Forest Song)

Aeneid by Ivan Kotliarevsky

Zaporizka Sich (The Zaporizhian Host)

“Yak umru to pokhovaite...” (When I am dead, bury me...)

Chornobyl Disaster

Antonov AN-225 Mriya ("The Dream")

Yuzivka

Creative & Tech Online Institute

Медіа про дизайн, креатив і тех індустрії

Ukrainski sichovi striltsi (The Ukrainian Sich Riflemen, or the USS)

Lisova Pisnia (The Forest Song)

Yuzivka

Antonov AN-225 Mriya ("The Dream")

“Plyve kacha po Tysyni...” (“Swims the duckling, on the Tysa...”)

Holodomor

“Smilyvi zavzhdy maiut shchastia” (“The brave always have happiness”)

Crimean Tatars, Karaites and Krymchaks (qırımlılar, qaraylar)

Antonov AN-225 Mriya ("The Dream")

Yuzivka

Peresopnytske Yevanheliie (The Peresopnytsia Gospel)

Yrii (/'irij/: iriy), yndyk (/in'dik/: turkey) and yrod (/'irod/: Herod)

Volia — collective concept, most often translated as Freedom

Yizhak protytankovyi (Czech hedgehog)

Khreshchenia Rusi (Christianization of Kyivan Rus’)